By Bree DeRoche

As with any great adventure, it began with a carefully orchestrated plan. Funds carefully procured and squirreled away, third-world-travel immunisation shots and pills carefully administered, maps carefully studied and marked up, travel guides carefully dog-eared and underlined, dates carefully selected.

My carefully selected date, at least six months in the planning, to fly into Jakarta was: 14 May 1998. A perfect day. A blue-sky day. A day hostile riots erupted throughout the city after four students were shot dead by police at Trisakti University during a demonstration two days prior.

Oblivious to current events, I soared blissfully overhead in Indonesian airspace, the sky a dazzling shade of azure. I noticed the heavy shroud of cloud cover as we approached the verdant, volcanic island of Java. There was a great deal of buzz in-cabin, staff zipped back and forth up the isles, there were several announcements over the intercom, but as we were flying into Jakarta, not Bali, the announcements were in Indonesian, so I didn’t catch what was going on. It didn’t help, either, that I was off my head on opiates.

Having been horrendously sick with the flu for days pre-departure, with sweats and fevers, yet had no flexibility on my inflexible Super Saver ticket to change my flights, Mum had given me the strongest pain killers she could find in the medicine cabinet to help ease the aches and nausea until I could check into a nice quiet hotel in Jakarta and recuperate for a couple days before hitting the open road with my backpack. I think they’d been prescribed to my sister after she had had her wisdom teeth out and the heavy narcotic base had me in feeling as though my head, soft and fluffy, was floating comfortably in mid-air a few centimetres above my shoulders.

It wasn’t until we started our decent that I noticed the ‘clouds’ covering the capital seemed to be emanating from little funnels coming from the ground and in my opiate daze – calm and serene, far from the madding crowd – I realised that the city of Jakarta was on fire.

It was the beginning of the Fall of Suharto. There was rampant unemployment across Indonesia, food shortages and the rupiah had taken a nose dive, causing costs to skyrocket. Students had taken to the streets in protest of Suharto. The riots rapidly turned into a pogrom, a violet mob attack directed against the ethnic-Chinese, who were made into scapegoats. Rioters were attacking homes and businesses of Chinese-Indonesians, in mob-like clusters, killing innocent people and destroying property.

It was the beginning of the Fall of Suharto. There was rampant unemployment across Indonesia, food shortages and the rupiah had taken a nose dive, causing costs to skyrocket. Students had taken to the streets in protest of Suharto. The riots rapidly turned into a pogrom, a violet mob attack directed against the ethnic-Chinese, who were made into scapegoats. Rioters were attacking homes and businesses of Chinese-Indonesians, in mob-like clusters, killing innocent people and destroying property.

The Arrival gates were manic. Passengers, staff, air crew, and police and soldiers with enormous semi-automatic weaponry darted back and forth in a state of absolute hysteria. I approached the bus terminal to buy a ticket into Jakarta and the counter attendant screamed over the hubbub, “Big riots! No Jakarta! You go Bogor!” – and with that, I was shuffled onto the first bus leaving the city, which departed 11 minutes later.

On the bus, as we approached the smoking city, heading towards the main arterial that would take us out of the city, the traffic slowed. Bumper to bumper we inched along. I could hear screams in the distance and see individual little infernos licking up between houses. Then the bus came to a complete standstill and armed bandits ran out into the road, targeting the vehicle directly in front of us, and in a mob of six or so, rocked it back and forth, back and forth, until they rolled it on its back like a beetle, doused it in fuel and set it alight.

There were screams and hysteria aboard the bus. Mothers smothered children into their bodies, old women cried. The men grabbed me, the only Australian among the 30 or so terrified Indonesians, and the two other westerners, Dutch backpacking brothers, and stuffed us down the back of the bus, out of sight, to prevent our big white moon faces from peering out the windows and drawing attention to the vehicle.

More screams and the bus was boarded by several gun-flailing bandits. “Kami adalah siswa! Kami adalah siswa!” bleated the terrified bus driver. We’re students. The bandits scanned the rows of passengers and I felt a firm hand pushed my head deeper into the vinyl seats, keeping me out of sight, to avoid any possible reason for aggravating the hostile pack on this wild rampage of terror. I was thankful for my lingering opiate high, which seemed create a buffer between me and the terror, almost like I was watching the whole thing from a distance … like on a television set. Yet I was also regretting the fact that, in my semi-doped state, I’d zippered by money belt, containing passport and cash, into a side pocket in my backpack, which was now stuffed in a locker over head. All I kept thinking was, When they open fire, do I try to grab my backpack or just run for my life?

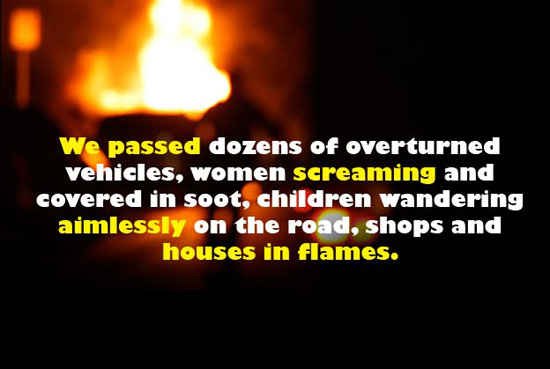

What seemed like an eternity later, but was probably only seconds, the rioters nodded and retreated, and I felt the collective sign as they leapt off the bus. Not only that, the bandits then directed our bus through the traffic, past the flaming vehicle they’d just ignited in front of us, carving out a narrow passage between the cars and debris for us to squeeze through – and the metal bus literally scraped and squealled against the sides of other vehicles – to get to the turn off to Bogor, 100 metres down the road. We passed dozens of overturned vehicles, women screaming and covered in soot, children wandering aimlessly on the road, shops and houses in flames. Gun-toting madmen crawled over the scene, pushing civilians, throwing kerosene bombs, but we were “siswa”, students, so we were allowed to pass.

As we made the turn off, driving under the swinging overhead sign reading ‘Bogor’, I can’t say what I felt was a sense of relief, as the fury continued to rage behind us: trucks being overturned, fireballs flying, children screaming, but I felt an all-consuming feeling of divine intervention – or possibly blind dumb luck – to have stumbled onto that bus, with those good people who risked their own safety to keep me safe. One kindly old gent on the bus even went so far, once we reached the safety of Bogor, to walk me by hand to a tourist hotel and make sure I checked in safety.

It was only later that I heard the devastating statistics. As many as 5000 people were killed and 500 women were mass gang-raped. There were rumours that elements of the Indonesia military special forces (Kopassus) were involved. To the people on that bus, I owe a debt of gratitude for having made it out of the city alive … because, holy sh*t, I thought I was going to die.

————————————————————————————————

“A thing is not necessarily true because a man dies for it.” — Oscar Wilde

————————————————————————————————

Writer’s Bio: Bree DeRoche travelled the globe for years with nothing but a dusty backpack and blissful ignorance before finding herself on the scariest trip of all: motherhood. Based in Melbourne, Australia, she’s a writer, editor and single mother of two. You can check out her blog, Beware of Falling Coconuts, or catch her on Twitter.

Writer’s Bio: Bree DeRoche travelled the globe for years with nothing but a dusty backpack and blissful ignorance before finding herself on the scariest trip of all: motherhood. Based in Melbourne, Australia, she’s a writer, editor and single mother of two. You can check out her blog, Beware of Falling Coconuts, or catch her on Twitter.

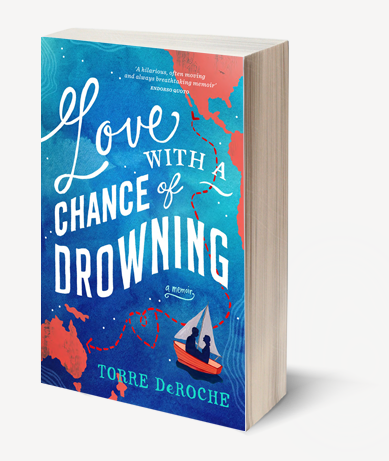

Torre DeRoche is the author of two travel memoirs, Love with a Chance of Drowning (2013) and The Worrier’s Guide to the End of the World (due out September 2017). She has written for The Atlantic, The Guardian Travel, The Sydney Morning Herald, Emirates, and two Lonely Planet anthologies.

7 Response Comments

Ohmygod. You really were almost going to die. That story is insane! Luck was definitely on your side that day.

This is horrifying. As Australians, we are lucky to be spared from this kind of war zone, but this is a reality for many people around the world. These images are going to stay with me for a long time.

I’m so glad I’m reading this story NOW rather than when you were traveling the globe for all those years. There are things a mother just shouldn’t know – and you knew that too! Great read! XX

When I reached the end of this story I realised that I was clutching my throat and had tears of terror in my eyes. I can only imagine what it would have been like for you to experience it.

It was one of those moments of travel where you seem to be operating on high adrenaline. No time to think. No way to escape. Just put your life in the hands of the gods!

That was a tense post. I can’t even begin to imagine what I would do if faced with the same situation! You must have been terrified.

Holy mother! That was something else. I think I would have just given up…